A few months ago, we’ve witnessed Phoenix team establishing 2 millions simultaneous connections on a single server. In the process, they also discovered and removed some bottlenecks. The whole process is documented in this excellent post. This achievement is definitely great, but reading the story begs a question: do we really need a bunch of expensive servers to study the behaviour of our system under load?

In my opinion, many issues can be discovered and tackled on a developer’s machine, and in this post, I’ll explain how. In particular, I’ll discuss how to programmatically “drive” a Phoenix socket, talk a bit about the transport layer, and cap it off by creating a half million of Phoenix sockets on my dev machine and explore the effects of process hibernation on memory usage.

The goal

The main idea is fairly simple. I’ll develop a helper SocketDriver module, which will allow me to create a Phoenix socket in a separate Erlang process, and then control it by sending it channel-specific messages.

Assuming we have a Phoenix application with a socket and a channel, we’ll be able to create a socket in a separate process by invoking:

iex(1)> {:ok, socket_pid} = SocketDriver.start_link(

SocketDriver.Endpoint,

SocketDriver.UserSocket,

receiver: self

)

The receiver: self bit specifies that all outgoing messages (the ones sent by the socket to the other side) will be sent as plain Erlang messages to the caller process.

Now I can ask the socket process to join the channel:

iex(2)> SocketDriver.join(socket_pid, "ping_topic")Then, I can verify that the socket sent the response back:

iex(3)> flush

{:message,

%Phoenix.Socket.Reply{payload: %{"response" => "hello"},

ref: #Reference<0.0.4.1584>, status: :ok, topic: "ping_topic"}}Finally, I can also push a message to the socket and verify the outgoing message:

iex(4)> SocketDriver.push(socket_pid, "ping_topic", "ping", %{})

iex(5)> flush

{:message,

%Phoenix.Socket.Message{event: "pong", payload: %{}, ref: nil,

topic: "ping_topic"}}With such driver I can now easily create a bunch of sockets from the iex shell and play with them. Later on you’ll see a simple demo, but let’s first explore how can such driver be developed.

Possible approaches

Creating and controlling sockets can easily be done with the help of the Phoenix.ChannelTest module. Using macros and functions, such as connect/2, subscribe_and_join/4 and push/3, you can easily create sockets, join channels, and push messages. After all, these macros are made precisely for the purpose of programmatically driving sockets in unit tests.

This approach should work nicely in unit tests, but I’m not sure it’s appropriate for load testing. The most important reason is that these functions are meant to be invoked from within the test process. This is actually perfect for unit tests, but in a load test I’d like to be closer to the real thing. Namely I’d like to run each socket in a separate process, and at that point the amount of housekeeping I need to do increases, and I’m practically implementing a Phoenix socket transport (I’ll explain what this means in a minute).

In addition, Phoenix.ChannelTest seems to rely on some internals of sockets and channels, and its functions create one %Socket{} struct per each connected client, something which is not done by currently existing Phoenix transports.

So instead, I’ll implement SocketDriver as a partial Phoenix transport, namely a GenServer that can be used to create and control a socket. This will allow me to be closer to existing transports. Moreover, it’s an interesting exercise to learn something about Phoenix internals. Finally, such socket driver can be used beyond load testing purposes, for example to expose different access points which can exist outside of Cowboy and Ranch.

Sockets, channels, transports, and socket driver

Before going further, let’s discuss some terminology.

The idea of sockets and channels is pretty simple, yet very elegant. A socket is an abstracted long-running connection between the client and the server. Messages can be wired through websocket, long polling, or practically anything else.

Once the socket is established, the client and the server can use it to hold multiple conversations on various topic. These conversations are called channels, and they amount to exchanging messages and managing channel-specific state on each side.

The corresponding process model is pretty reasonable. One process is used for the socket, and one for each channel. If a client opens 2 sockets and joins 20 topics on each socket, we’ll end up with 42 processes: 2 * (1 socket process + 20 channel processes).

A Phoenix socket transport is the thing that powers the long running connection. Owing to transports, Phoenix.Socket, Phoenix.Channel, and your own channels, can safely assume they’re operating on a stateful, long-running connection regardless of how this connection is actually powered.

You can implement your own transports, and thus expose various communication mechanisms to your clients. On the flip side, implementing a transport is somewhat involved, because various concerns are mixed in this layer. In particular, a transport has to:

- Manage a two-way stateful connection

- Accept incoming messages and dispatch them to channels

- React to channel messages and dispatch responses to the client

-

Manage the mapping of topics to channel processes in a

HashDict(and usually the reverse mapping as well) - Trap exits, react to exits of channel processes

- Provide adapters for underlying http server libraries, such as Cowboy

In my opinion that’s a lot of responsibilities bundled together, which makes the implementation of a transport more complex than it should be, introduces some code duplication, and makes transports less flexible than they could be. I shared these concerns with Chris and José, so there are chances this might be improved in the future.

As it is, if you want to implement a transport, you need to tackle the points above, save possibly one: in case your transport doesn’t need to be exposed through an http endpoint, you can skip the last point, i.e. you don’t need to implement Cowboy (or some other web library) adapter. This effectively means you’re not a Phoenix transport anymore (because you can’t be accessed through the endpoint), but you’re still able to create and control a Phoenix socket. This is what I’m calling a socket driver.

The implementation

Given the list above, the implementation of SocketDriver is fairly straightforward, but somewhat involved, so I’ll refrain from step-by-step explanation. You can find the full code here, with some basic comments included.

The gist of it is, you need to invoke some Phoenix.Socket.Transport functions at proper moments. First, you need to invoke connect/6 to create the socket. Then, for every incoming message (i.e. a message that was sent by the client), you need to invoke dispatch/3. In both cases, you’ll get some channel-specific response which you must handle.

Additionally, you need to react to messages sent from channel processes and the PubSub layer. Finally, you need to detect terminations of channel processes and remove corresponding entries from your internal state.

I should mention that this SocketDriver uses a non-documented Phoenix.ChannelTest.NoopSerializer - a serializer that doesn’t encode/decode messages. This will keep things simple, but it will also remove the encoding/decoding job out of the tests.

Creating 500k sockets & channels

With SocketDriver in place, we can now easily create a bunch of sockets locally. I’ll do this in the prod environment to mimic the production more closely.

A basic Phoenix server with a simple socket/channel can be found here. I need to compile it in prod (MIX_ENV=prod mix compile), and then I can start it with:

MIX_ENV=prod PORT=4000 iex --erl "+P 10000000" -S mix phoenix.server

The –erl “+P 10000000” option increases the default maximum number of processes to 10 millions. I plan to create 500k sockets, so I need a bit more than a million of processes, but to be on the safe side, I’ve chosen a much larger number. Creating sockets is now as simple as:

iex(1)> for i <- 1..500_000 do

# Start the socket driver process

{:ok, socket} = SocketDriver.start_link(

SocketDriver.Endpoint,

SocketDriver.UserSocket

)

# join the channel

SocketDriver.join(socket, "ping_topic")

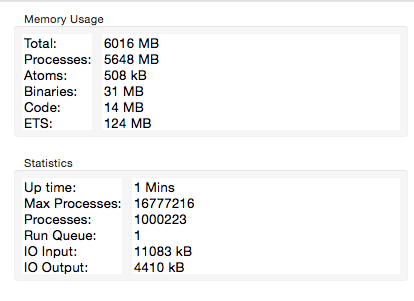

endIt takes about a minute on my machine to create all these sockets and then I can fire up the observer. Looking at the System tab, I can see that about a million of processes are running, as expected:

I should also mention that I’ve changed the default logger level setting to :warn in prod. By default, this setting is :info which will dump a bunch of logs to the console. This in turn might affect the throughput of your load generator, so I raised this level to mute needless messages.

Also, to make the code runnable out of the box, I removed the need for the prod.secret.exs file. Obviously a very bad practice, but this is just a demo, so we should be fine. Just keep in mind to avoid developing any production on top of my (or your own) hacky experiments :-)

Hibernating processes

If you take a closer look at the image above, you’ll see that the memory usage of about 6GB is somewhat high, though I wouldn’t call it excessive for so many created sockets. I’m not sure whether Phoenix team did some memory optimizations, so there’s possibility this overhead might be reduced in future versions.

As it is, let’s see whether process hibernation can help us reduce this memory overhead. Note that this is a shallow experiment, so don’t draw any hard conclusions. This will be more like a simple demo of how we can quickly gain some insights by creating a bunch of sockets on our dev box, and explore various routes locally.

First a bit of theory. You can reduce the memory usage of the process by hibernating it with :erlang.hibernate/3. This will trigger the garbage collection of the process, shrink the heap, truncate the stack, and put the process in the waiting state. The process will be awoken when it receives a message.

When it comes to GenServer, you can request the hibernation by appending the :hibernate atom to most of return tuples in your callback functions. So for example instead of {:ok, state} or {:reply, response, state}, you can return {:ok, state, :hibernate} and {:reply, response, state, :hibernate} from init/1 and handle_call/3 callbacks.

Hibernation can help reducing memory usage of processes which are not frequently active. You pay some CPU price, but you get some memory in return. Like most other things in life, hibernation is a tool, not a silver bullet.

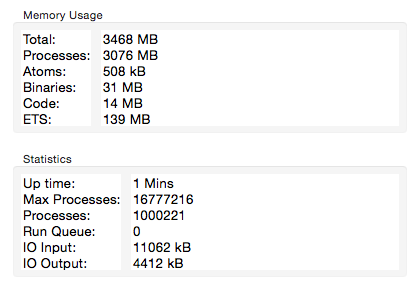

So let’s see whether we can gain something by hibernating socket and channel processes. First, I’ll modify SocketDriver by adding :hibernate to init, handle_cast, and handle_info callbacks in SocketDriver. With these changes, I get following results:

This is about 40% less memory used, which seems promising. It’s worth mentioning that this is not a conclusive test. I’m hibernating my own socket driver, so I’m not sure whether the same saving would happen in the websocket transport, which is not GenServer based. However, I’m somewhat more certain that hibernating might help with long polling, where a socket is driven by a GenServer process, which is similar to SocketDriver (in fact, I consulted Phoenix code a lot while developing SocketDriver).

In any case, these tests should be retried with real transports, which is one reason why this experiment is somewhat contrived and non-conclusive.

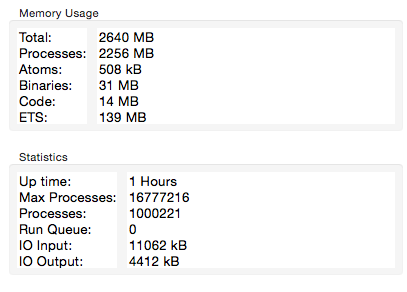

Regardless, let’s move on and try to hibernate channel processes. I modified deps/phoenix/lib/phoenix/channel/server.ex to make the channel processes hibernate. After recompiling deps and creating 500k sockets, I noticed additional memory saving of 800MB:

After hibernating sockets and channels, the memory usage is reduced by more than 50%. Not too shabby :-)

Of course, it’s worth repeating that the hibernation comes with a price which is CPU usage. By hibernating, we force some work to be done immediately, so it should be used carefully and the effects on performance should be measured.

Also, let me stress again that this is a very shallow test. At best these results can serve as an indication, a clue as to whether hibernation might help. Personally, I think it’s a useful hint. In a real system the state of your channels might be more complex, and they might perform various transformations. Thus, in some cases, occasional hibernation might bring some nice savings. Therefore, I think Phoenix should allow us to request hibernation of our channel processes through callback tuples.

Conclusion

The main point of this article is that by driving Phoenix sockets, you can quickly gain some insights on how your system behaves under a more significant load. You can start the server, kick off some synthetic loader, and observe the system’s behaviour. You can gather feedback and try some alternatives more quickly, and in the process you don’t need to shell out tons of money for beefy servers, nor spend a lot of time tweaking the OS settings to accommodate a lot of open network sockets.

Of course, don’t mistake this for a full test. While driving sockets can help you get some insights, it doesn’t paint the whole picture, because network I/O is bypassed. Moreover, since the loader and the server are running on the same machine, thus competing for the same resources, the results might be skewed. An intensive loader might affect the performance of the server.

To get the whole picture, you’ll probably want to run final end-to-end tests on production-like server with separate client machines. But you can do this less often and be more confident that you’ve handled most problems before you moved to the more complicated stage of testing. In my experience, a lot of low-hanging fruit can be picked by exercising the system locally.

Finally, don’t put too much faith in synthetic tests, because they will not be able to completely simulate the chaotic and random patterns of the real life. That doesn’t mean such tests are useless, but they’re definitely not conclusive. As the old saying goes: “There’s no test like production!” :-)

Comments