That is indeed the question! Whether it is better to keep everything in a single process, or to have a separate process for every piece of state we need to manage? In this post I’ll talk a bit about using and not using processes. I’ll also discuss how to separate complex stateful logic from concerns such as temporal behaviour and cross process communication.

But before starting, since this is going to be a long article, I want to immediately share my main points:

- Use functions and modules to separate thought concerns.

- Use processes to separate runtime concerns.

- Do not use processes (not even agents) to separate thought concerns.

The construct “thought concern” here refers to ideas which exist in our mind, such as order, order item, and product for example. If those concepts are more complex, it’s worth implementing them in separate modules and functions to separate different concerns and keep each part of our code focused and concise.

Using processes (e.g. agents) for this is a mistake I see people make frequently. Such approach essentially sidesteps the functional part of Elixir, and instead attempts to simulate objects with processes. The implementation will very likely be inferior to the plain FP approach (or even an equivalent in an OO language). Keep in mind that there is a price associated with processes (memory and communication overhead). Therefore, reach for processes when there are some tangible benefits which justify that price. Code organization is not among those benefits, so that’s not a good reason for using processes.

Processes are used to address runtime concerns - properties which can be observed in a running system. For example, you’ll want to reach for multiple processes when you want to prevent a failure of one job to affect other activities in the system. Another motivation is when you want to introduce a potential for parallelism, allowing multiple jobs to run simultaneously. This can improve your performance, and open up potential for scaling in both directions. There are some other, less common cases for using processes, but again - separation of thought concerns is not one of them.

An example

But how do we manage a complex state then, if not with agents and processes? Let me illustrate the idea through a simple domain model of a reduced, and a slightly modified version of the blackjack game. The code I’ll show you (available here) powers a single round on the blackjack table.

A round is basically a sequence of hands, with each hand belonging to a different player. The round starts with the first hand. The player is initially given two cards and then makes a move: take one more card (a hit), or take a stand. In the former case, another card is given to the player. If the score of the player’s hand is greater than 21, the player is busted. Otherwise, the player can take another move (hit or stand).

The score of the hand is the sum of all the values of the cards, with numerical ranks (2-10) having their respective values, while jack, queen, and king have the value of 10. An ace card can be valued as 1 or as 11, whichever gives a better (but not busted) score.

The hand is finished if the player stands or busts. When a hand is finished, the round moves to the next hand. Once all the hands have been played, the winners are non-busted hands with the highest score.

To keep things simple, I didn’t deal with concepts such as dealer, betting, insurance, splitting, multiple rounds, people joining or leaving the table.

Process boundaries

So, we need to keep track of different types of states which change over time: a deck of cards, hands of each player, and the state of the round. A naive take on this, would be use multiple processes. We could have one process per each hand, another process for the deck of cards, and the “master” process that drives the entire round. I see people occasionally take similar approach, but I’m not at all convinced that it’s the proper way to go. The main reason is that the game is in its nature highly synchronized. Things happen one by one in a well defined order: I get my cards, I make one or more moves, and when I’m done, you’re next. At any point in time, there’s only one activity happening in a single round.

Using multiple processes to power a single round is therefore going to do more harm than good. With multiple processes, everything is concurrent, so you need to make additional effort to synchronize all the actions. You’ll also need to pay attention to proper process termination and cleanup. If you stop the round process, you need to stop all the associated processes as well. The same should hold in the case of a crash: an exception in a round, or a deck process should likely terminate everything (because the state is corrupt beyond repair). Maybe a crash of a single hand could be isolated, and that might improve fault-tolerance a bit, but I think this is a too fine level to be concerned about fault isolation.

So in this case, I see many potential downsides, and not a lot of benefits for using multiple processes to manage the state of a single round. However, different rounds are mutually independent. They have their own separate flows, hold their separate states, share nothing in common. Thus, managing multiple rounds in a single process is counter productive. It will increase our error surface (failure of one round will take everything down), and possibly lead to worse performance (we’re not using multiple cores), or bottlenecks (a long processing in a single round will paralyze all the others). There are clear wins if we’re running different rounds in separate processes, so that decision is a no-brainer :-)

I frequently say in my talks, that there’s a huge potential for concurrency in complex systems, so we’ll use a lot of processes. But to reap those benefits, we need to use processes where they make sense.

So, all things considered, I’m pretty certain that a single process for managing the entire state of a single round is the way to go. It would be interesting to see what would change if we introduced the concept of a table, where rounds are played perpetually, and players change over time. I can’t say for certain at this point, but I think it’s an interesting exercise in case you want to explore it :-)

Functional modeling

So, how can we separate different concerns without using multiple processes? By using functions and modules, of course. If we spread different parts of the logic across different functions, give those functions proper names, and maybe organize them into properly named modules, we can represent our ideas just fine, without needing to simulate objects with agents.

Let me show you what I mean by walking you through each part of my solution, starting with the simplest one.

A deck of cards

The first concept I want to capture is a deck of card. We want to model a standard deck of 52 cards. We want to start with a shuffled deck, and then be able to take cards from it, one by one.

This is certainly a stateful concept. Every time we take a card, the state of the deck changes. Despite that, we can implement the deck with pure functions.

Let me show you the code. I decided to represent the deck as a list of cards, each card being a map holding a rank and a suit. I can generate all the cards during compilation:

@cards (

for suit <- [:spades, :hearts, :diamonds, :clubs],

rank <- [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, :jack, :queen, :king, :ace],

do: %{suit: suit, rank: rank}

)

Now, I can add the shuffle/0 function to instantiate a shuffled deck:

def shuffled(), do:

Enum.shuffle(@cards)

And finally, take/1, which takes the top card from the deck:

def take([card | rest]), do:

{:ok, card, rest}

def take([]), do:

{:error, :empty}

The take/1 function returns either {:ok, card_taken, rest_of_the_deck}, or {:error, :empty}. Such interface forces a client (a user of the deck abstraction) to explicitly decide how to deal with each case.

Here’s how we can use it:

deck = Blackjack.Deck.shuffled()

case Blackjack.Deck.take(deck) do

{:ok, card, transformed_deck} ->

# do something with the card and the transform deck

{:error, :empty} ->

# deck is empty -> do something else

endThis is an example of what I like to call a “functional abstraction”, which is a fancy name for:

- a bunch of related functions,

- with descriptive names,

- which exhibit no side-effects,

- and are maybe extracted in a separate module

This to me is what corresponds to classes and objects in OO. In an OO language, I might have a Deck class with corresponding methods, here I have a Deck module with corresponding functions. Preferably (though not always worth the effort), functions only transform data, without dealing with temporal logic or side-effects (cross-process messaging, database, network requests, timeouts, …).

It’s less important whether these functions are sitting in a dedicated module. The code for this abstraction is quite simple and it’s used in only one place. Therefore, I could have also defined private shuffled_deck/0 and take_card/1 functions in the client module. This is in fact what I frequently do if the code is small enough. I can always extract later, if things become more complicated.

The important point is that the deck concept is powered by pure functions. No need to reach for an agent to manage a deck of cards.

The complete code of the module is available here.

A blackjack hand

The same technique can be used to manage a hand. This abstraction keeps track of cards in the hand. It also knows how to calculate the score, and determine the hand status (:ok or :busted). The implementation resides in the Blackjack.Hand module.

The module has two functions. We use new/0 to instantiate the hand, and then deal/2 to deal a card to the hand. Here’s an example that combines a hand and a deck:

# create a deck

deck = Blackjack.Deck.shuffled()

# create a hand

hand = Blackjack.Hand.new()

# draw one card from the deck

{:ok, card, deck} = Blackjack.Deck.take(deck)

# give the card to the hand

result = Blackjack.Hand.deal(hand, card)

The result of deal/2 will be in shape of {hand_status, transformed_hand}, where hand_status is either :ok or :busted.

Blackjack round

This abstraction, powered by the Blackjack.Round module, ties everything together. It has following responsibilities:

- keeping the state of the deck

- keeping the state of all the hands in a round

- deciding who’s the next player to move

- accepting and interpreting player moves (hit/stand)

- taking cards from the deck and passing them to current hand

- computing the winner, once all the hands are resolved

The round abstraction will follow the same functional approach as deck and hand. However, there’s an additional twist here, which concerns separation of the temporal logic. A round takes some time and requires interaction with players. For example, when the round starts, the first player needs to be informed about the first two card they got, and then they need to be informed that it’s their turn to make a move. The round then needs to wait until the player makes the move, and only then can it step forward.

My impression is that many people, experienced Erlangers/Elixorians included, would implement the concept of a round directly in a GenServer or :gen_statem. This would allow them to manage the round state and temporal logic (such as communicating with players) in the same place.

However, I believe that these two aspects need to be separated, since they are both potentially complex. The logic of a single round is already somewhat involved, and it can only get worse if we want to support additional aspects of the game, such as betting, splitting, or dealer player. Communicating with players has its own challenges if we want to deal with netsplits, crashes, slow or unresponsive clients. In these cases we might need to support retries, maybe add some persistence, event sourcing, or whatnot.

I don’t want to combine these two complex concerns together, because they’ll become entangled, and it will be harder to work with the code. I want to move temporal concerns somewhere else, and have a pure domain model of a blackjack round.

So instead I opted for an approach I don’t see that often. I captured the concept of a round in a plain functional abstraction.

Let me show you the code. To instantiate a new round, I need to call start/1:

{instructions, round} = Blackjack.Round.start([:player_1, :player_2])The argument I need to pass is the list of player ids. These can be arbitrary terms, and will be used by the abstraction for various purposes:

- instantiating a hand for each player

- keeping track of the current player

- issuing notifications to players

The function returns a tuple. The first element of the tuple is a list of instructions. In this example, it will be:

[

{:notify_player, :player_1, {:deal_card, %{rank: 4, suit: :hearts}}},

{:notify_player, :player_1, {:deal_card, %{rank: 8, suit: :diamonds}}},

{:notify_player, :player_1, :move}

]The instructions are the way the abstraction informs its client what needs to be done. As soon as we start the round, two cards are given to the first hand, and then the round instance awaits for the move by the player. So in this example, the abstraction instructs us to:

- notify player 1 that it got 4 of hearts

- notify player 1 that it got 8 of diamonds

- notify player 1 that it needs to make a move

It is the responsibility of the client code to actually deliver these notifications to concerned players. The client code can be say a GenServer, which will send messages to player processes. It will also wait for the players to report back when they want to interact with the game. This is temporal logic, and it’s completely kept outside of the Round module.

The second element of the returned tuple, called round, is the state of the round itself. It’s worth noting that this data is typed as opaque. This means that client shouldn’t read the data inside the round variable. Everything the client needs will be delivered in the instruction list.

Let’s take this round instance one step further, by taking another card as player 1:

{instructions, round} = Blackjack.Round.move(round, :player_1, :hit)I need to pass the player id, so the abstraction can verify if the right player is making the move. If I pass the wrong id, the abstraction will instruct me to notify the player that it’s not their turn.

Here are the instructions I got:

[

{:notify_player, :player_1, {:deal_card, %{rank: 10, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_1, :busted},

{:notify_player, :player_2, {:deal_card, %{rank: :ace, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_2, {:deal_card, %{rank: :jack, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_2, :move}

]This list tells me that player 1 got 10 of spades. Since it previously had 4 of hearts and 8 of diamonds, the player is busted, and the round immediately moves to the next hand. The client is instructed to notify player 2 that it got two cards, and that it should make a move.

Let’s make a move on behalf of player 2:

{instructions, round} = Blackjack.Round.move(round, :player_2, :stand)

# instructions:

[

{:notify_player, :player_1, {:winners, [:player_2]}}

{:notify_player, :player_2, {:winners, [:player_2]}}

]Player 2 didn’t take another card, and therefore its hand is completed. The abstraction immediately resolves the winner and instructs us to inform both players about the outcome.

Let’s take a look at how Round builds nicely on top of Deck and Hand abstractions. The following function from the Round module takes a card from the deck, and gives it to the current hand:

defp deal(round) do

{:ok, card, deck} =

with {:error, :empty} <- Blackjack.Deck.take(round.deck), do:

Blackjack.Deck.take(Blackjack.Deck.shuffled())

{hand_status, hand} = Hand.deal(round.current_hand, card)

round =

%Round{round | deck: deck, current_hand: hand}

|> notify_player(round.current_player_id, {:deal_card, card})

{hand_status, round}

end

We take a card from the deck, optionally using the new deck if the current one is exhausted. Then we pass the card to the current hand, update the round with the new hand and deck status, add a notification instruction about the given card, and return the hand status (:ok or :busted) and the updated round. No extra process is involved in the process :-)

The notify_player invocation is a simple one-liner which pushes a lot of complexity away from this module. Without it, we’d need to send a message to some other process (say another GenServer, or a Phoenix channel). We’d have to find that process somehow, and consider cases when this process isn’t running. A lot of extra complexity would have to be bundled together with the code which models the flow of the round.

But thanks to the instructions mechanism, none of this happens, and the Round module stays focused on the rules of the game. The notify_player function will store the instruction entry. Then later, before returning, a Round function will pull all pending instructions, and return them separately, forcing the client to interpret those instructions.

As an added benefit, the code can now be driven by different kinds of drivers (clients). In the examples above, I drove it manually from the session. Another example is driving the code from tests. This abstraction can now be easily tested, without needing to produce or observe side-effects.

Process organization

With the basic pure model complete, it’s time to turn our attention to the process side of things. As I discussed earlier, I’ll host each round in a separate process. I believe this makes sense, since different rounds have nothing in common. Therefore, running them separately gives us better efficiency, scalability, and error isolation.

Round server

A single round is managed by the Blackjack.RoundServer module, which is a GenServer. An Agent could also serve the purpose here, but I’m not a fan of agents, so I’ll just stick with GenServer. Your preferences may differ, of course, and I totally respect that :-)

In order to start the process, we need to invoke the start_playing/2 function. This name is chosen instead of a more common start_link, since start_link by convention links to the caller process. In contrast, start_playing will start the round somewhere else in the supervision tree, and the process will not be linked to the caller.

The function takes two arguments: the round id, and the list of players. The round id is an arbitrary unique term which needs to be chosen by the client. The server process will be registered in an internal Registry using this id.

Each entry in the list of players is a map describing a client side of the player:

@type player :: %{id: Round.player_id, callback_mod: module, callback_arg: any}

A player is described with its id, a callback module, and a callback arg. The id is going to be passed to the round abstraction. Whenever the abstraction instructs the server to notify some player, the server will invoke callback_mod.some_function(some_arguments), where some_arguments will include round id, player id, callback_arg, and additional, notification-specific arguments.

The callback_mod approach allows us to support different kinds of players such as:

- players connected through HTTP

- players connected through a custom TCP protocol

-

a player in the

iexshell session - automatic (machine) players

We can easily handle all these players in the same round. The server doesn’t care about any of that, it just invokes callback functions of the callback module, and lets the implementation do the job.

The functions which must be implement in the callback module are listed here:

@callback deal_card(RoundServer.callback_arg, Round.player_id,

Blackjack.Deck.card) :: any

@callback move(RoundServer.callback_arg, Round.player_id) :: any

@callback busted(RoundServer.callback_arg, Round.player_id) :: any

@callback winners(RoundServer.callback_arg, Round.player_id, [Round.player_id])

:: any

@callback unauthorized_move(RoundServer.callback_arg, Round.player_id) :: anyThese signatures reveal that the implementation can’t manage its state in the server process. This is an intentional decision, which practically forces the players to run outside of the round process. This helps us keeping the round state isolated. If a player crashes or disconnects, the round server still keeps running, and can handle the situation, for example by busting a player if they fail to move within a given time.

Another nice consequence of this design is that testing of the server is fairly straightforward. The test implements the notifier behaviour by sending itself messages from every callback. Testing then boils down to asserting/refuting particular messages, and invoking RoundServer.move/3 to make the move on behalf of the player.

Sending notifications

When functions from the Round module return the instruction list to the server process, it will walk through them, and interpret them.

The notifications themselves are sent from separate processes. This is an example where we can profit from extra concurrency. Sending notifications is a task which is separate from the task of managing the state of the round. The notifications logic might be burdened by issues such as slow or disconnected clients, so it’s worth doing this outside of the round process. Moreover, notifications to different players have nothing in common, so they can be sent from separate processes. However, we need to preserve the order of notifications for each player, so we need a dedicated notification process per each player.

This is implemented in the Blackjack.PlayerNotifier module, a GenServer based process whose role is to send notification to a single player. When we start the round server with the start_playing/2 function, a small supervision subtree is started which hosts the round server together with one notifier server per each player in the round.

When the round server plays a move, it will get a list of instructions from the round abstraction. The server will then forward each instruction to the corresponding notifier server which will interpret the instruction and invoke a corresponding M/F/A to notify the player.

Hence, if we need to notify multiple players, we’ll do it separately (and possibly in parallel). As a consequence, the total ordering of messages is not preserved. Consider the following sequence of instructions:

[

{:notify_player, :player_1, {:deal_card, %{rank: 10, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_1, :busted},

{:notify_player, :player_2, {:deal_card, %{rank: :ace, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_2, {:deal_card, %{rank: :jack, suit: :spades}}},

{:notify_player, :player_2, :move}

]

It might happen that player_2 messages arrives before player_1 is informed that it’s busted. But that’s fine, since those are two different players. The ordering of messages per each player is of course preserved, courtesy of player-specific notifier server process.

Before parting, I want to drive my point again: owing to the design and functional nature of the Round module, all this notifications complexity is kept outside of the domain model. Likewise, notification part is not concerned with the domain logic.

The blackjack service

The picture is completed in the form of the :blackjack OTP application (the Blackjack module). When you start the application, a couple of locally registered processes are started: an internal Registry instance (used to register round and notifier servers), and a :simple_one_for_one supervisor which will host process subtree for each round.

This application is now basically a blackjack service that can manage multiple rounds. The service is generic and not depending on a particular interface. You can use it with Phoenix, Cowboy, Ranch (for plain TCP), elli, or whatever else suits your purposes. You implement a callback module, start client processes, and start the round server.

You can see an example in the Demo module, which implements a simple auto player, a GenServer powered notifier callback, and a starting logic which starts the round with five players:

$ iex -S mix

iex(1)> Demo.run

player_1: 4 of spades

player_1: 3 of hearts

player_1: thinking ...

player_1: hit

player_1: 8 of spades

player_1: thinking ...

player_1: stand

player_2: 10 of diamonds

player_2: 3 of spades

player_2: thinking ...

player_2: hit

player_2: 3 of diamonds

player_2: thinking ...

player_2: hit

player_2: king of spades

player_2: busted

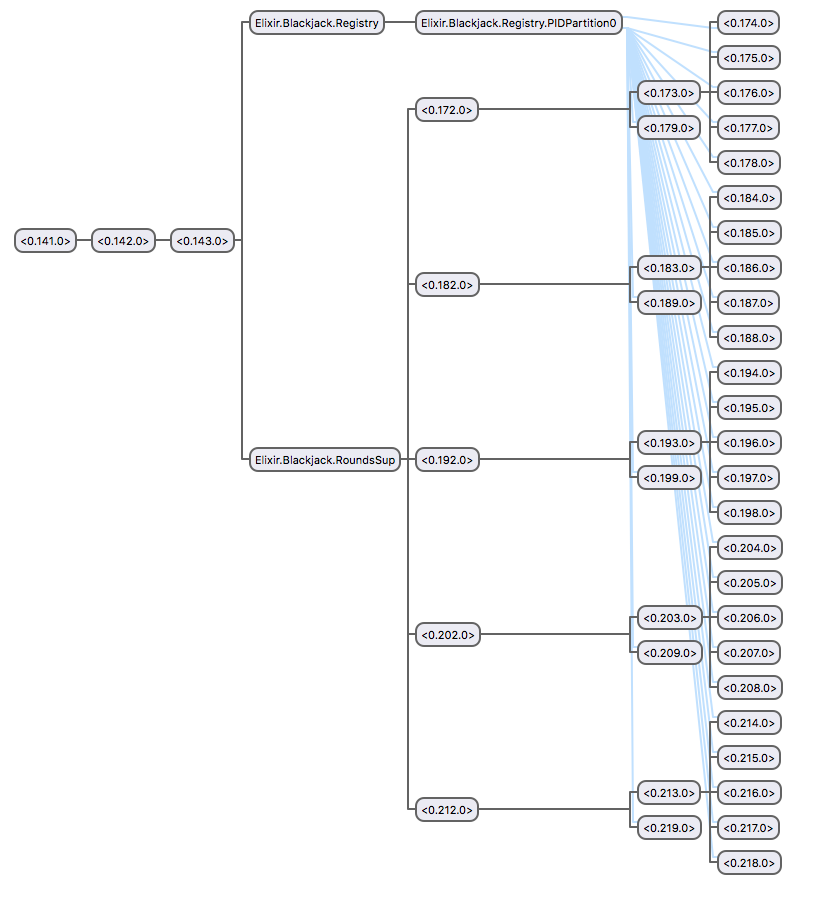

...Here’s how a supervision tree looks like when we have five simultaneous rounds, each with five players:

Conclusion

So, can we manage a complex state in a single process? We certainly can! Simple functional abstractions such as Deck and Hand allowed me to separate concerns of a more complex round state without needing to resort to agents.

That doesn’t mean we need to be conservative with processes though. Use processes wherever they make sense and bring some clear benefits. Running different rounds in separate processes improves scalability, fault-tolerance, and the overall performance of the system. The same thing applies for notification processes. These are different runtime concerns, so there’s no need to run them in the same runtime context.

If temporal and/or domain logic are complex, consider separating them. The approach I took allowed me to implement a more involved runtime behaviour (concurrent notifications) without complicating the business flow of the round. This separation also puts me in a nice spot, since I can now evolve both aspects separately. Adding the support for dealer, split, insurance, and other business concepts should not affect the runtime aspect significantly. Likewise, supporting netsplits, reconnects, player crashes, or timeouts should not require the changes in the domain logic.

Finally, it’s worth keeping the end goal in mind. While I didn’t go there (yet), I always planned for this code to be hosted in some kind of a web server. So some decisions are taken to support this scenario. In particular, the implementation of RoundServer, which takes a callback module for each player, allows me to hook up with different kinds of clients powered by various technologies. This keeps the blackjack service agnostic of particular libraries and frameworks (save for standard libraries and OTP of course), and completely flexible.

Comments